0. Motivation

Sometimes it is difficult to explain clearly security concepts to someone else, especially to non-technical people.Using comparisons and analogies, even if not 100% accurate, usually works better. Below are some analogies I’ve heard over the years and liked, that can make this easier and maybe even interesting.

1. Cryptographic hash function

Tech

As described here, a hash function is an algorithm that takes as input an arbitrary block of data (the “message”) and returns a fixed-size bit string called hash value, message digest or fingerprint. Its role is to detect with very high probability any accidental or intentional change of the message (Property 3). It has four properties:

- It is easy to compute the hash value for any given message.

- It is infeasible to generate a message that has a given hash.

- It is infeasible to modify a message without changing the hash.

- It is infeasible to find two different messages with the same hash.

A hash is easy to calculate (P1) but infeasible to reverse (P2), so it is a one way process.

Human

Think of how a coffee grinder works: it is easy to grind coffee beans into coffee powder, however it is unfeasible to revert coffee powder back to beans. Coffee beans are the data, the grinder is the hash function and the coffee powder is the message digest.

2. Diffie-Hellman key exchange

Tech

It is a method of exchanging secret keys. The D-H key exchange method allows two parties that have no prior knowledge of each other to jointly establish a shared secret key over an insecure communications channel. This is very important! The established key can then be used to encrypt subsequent communications. Mathematically, it is based on the discrete logarithm problem (a difficult problem with no efficient solving algorithms known).

Human

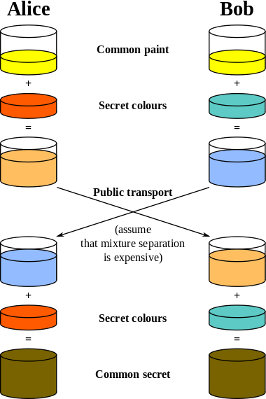

The D-H exchange algorithm can be easily illustrated using colors instead of large numbers. The following picture shows how two parties can generate an identical key that is almost impossible to reverse for another party that might have been listening in on them:

Explanation:

- Alice and Bob both agree on a color, yellow, which is public.

- They also both have a secret color each.

- Suppose an eavesdropper can intercept the transmitted color mix, she should separate it into yellow + something (for example, if yellow is the public colour), which is considered very expensive.

- After each party receives the mix as in the picture, each mix it also with their secret color, so both come to the same result. For the example in the picture, that colour woult be yellow + orange + blue, which will be used as the secret key. Nice!

3. Public/Private keys (for secrecy)

Tech

Public-key cryptography and asymmetric key algorithms concepts are explained here. The concepts of public and private keys can be sometimes confusing. The following (admittedly a bit simplified) analogy may help to better understand them.

Human

- The public key is similar to a padlock, which the owner can make any copies of it and distribute it to the people.

- The private key is the actual key that opens the padlock. Only the owner has it, and it has to be kept safe.

So the public key (the padlock) can be distributed anywhere, and if someone wants to send a message that only the owner of the padlock can read, he can put it in a box and close it with the padlock, and only the true owner will have the private key to open the box.

4. Public/Private keys (for authenticity)

Tech

Another usage of public/private keys is that they allow the owner to digitally sign a message with its private key, and everybody having his public key can verify the signature with it, and then read the message.

Human

This is similar to sealing of an envelope with a personal wax seal. The message can be opened and read by anyone, but the presence of the seal authenticates the sender.

5. Deriving keys from passwords

Explanation

Lots of programs we’re using to encrypt and protect our data (Wi-Fi Protected Access, WinZip, Word, TrueCrypt, EFS, ..) use very long keys (128 bits, 160 bits, 256 bits, …) for the encryption algorithms. But we don’t have to remember those exceedingly long keys. Insted we enter a password to secure things, and that same password to access them. The process of deriving a key from a password is standardized as Password-Based Key Derivation Function. Basically this applies a pseudo-random function (such as a cryptographic hash, or HMAC) to the input passphrase, along with a salt value and repeats the process many times to produce a derived key. Adding a salt reduces the ability to use precomputed hashes (rainbow tables).

6. Blind signatures

Tech

Blind signatures, introduced by David Chaum, are a form of digital signature, in which the content of a message is disguised (blinded) before it is signed. The resulting blind signature can be publicly verified against the original message in a similar manner as a regular digital signature. Blind signatures are typically employed in privacy-related protocols like digital cash schemes, that provide confidentiality.

Human

As an analogy, Alice has a letter which should be signed by an authority (say Bob), but Alice does not want to reveal the content of the letter to Bob. She can place the letter in an envelope lined with carbon paper and send it to Bob. Bob will sign the outside of the carbon envelope without opening it and then send it back to Alice. Alice can then open it to find the letter signed by Bob, but without Bob having seen its contents.

But how does this applies to digital cash for example? If Alice would make a purchase for an object using her bank account, the transaction would be registered, and the bank would know that Alice bought that specific object. If Alice wants to keep this anonymous, she would need some digital cash, signed by the bank, that she could spend at any seller, and the seller to be able to check the signature and withdraw the cash from the bank. The solution can be described as follows:

- Alice generates 100 digital banknotes, each with its own serial number and same value. She puts them each in an envelop with a carbon paper.

- The bank opens 99 of them, checks that each represent the same amount, and assume that the 100th one also represents the same amount.

- Then the bank signs the last envelope, without opening it, and the signature goes through the carbon paper on the (digital) banknote. Then sends it back to Alice.

- Alice opens the received envelope and extracts the banknote. Now Alice has an untraceable banknote signed by the bank, that she could pass to any seller in exchange for goods.

- The seller checks that the bank signature is valid, and the bank credits him the respective sum of money.

7. Zero knowledge proofs

Tech

A zero-knowledge protocol is an interactive method for one party to prove to another that he knows a secret, without actually revealing it. Sometimes this is a very desirable property to have. The story explaining the protocol ideas (as presented by Jean-Jacques Quisquater and others in their paper “How to Explain Zero-Knowledge Protocols to Your Children”) is described here.

Human

Besides the example presented on the link above with the Ali Baba cave, another classic example of usage of a Zero Knowledge protocol usually given in cryptography classes is as follows: imagine your friend is color-blind. You have two balls; one is red, one is green, but they are otherwise identical. To your friend they seem completely identical, and he is skeptical that they are actually distinguishable. You want to prove to him that they are in fact differently-colored. On the other hand, you do not want him to learn which is red and which is green. How do you do it?

- You give the two balls to your friend so that he is holding one in each hand. You can see the balls at this point, but you don’t tell him which is which.

- Your friend then puts both hands behind his back.

- Next, he either switches the balls between his hands, or leaves them be, with probability 1/2 each.

- Finally, he brings them out from behind his back.

- By looking at their colors, you can of course say with certainty whether or not he switched them, because you know their initial position.

- On the other hand, if they were the same color and hence indistinguishable, there is no way you could have guessed correctly with probability higher than 1/2.

If you repeat this a large number of times, your friend should become convinced that the balls are indeed differently colored, but he will not learn which is which (zero-knowledge proof).